OOP and Inheritance - the scourge of modern programming practices.

“OOP is a terrible paradigm, stop using inheritance, it’s bad practice” - this is something that you will hear around on the internet and through some ideologues. Yes, that was clickbait.

Is inheritance a bad design decision?

Not necessarily, if you understand how to architect systems and quantify the change distance and complexity stemming from inheritance decisions.

TL;DR This article explores reframing our mental model of code by applying graph theory to reveal hidden structural patterns, empowering more informed architectural decisions.

The conventional wisdom suggests limiting inheritance to one or two levels. When parent classes share substantial common variables or functionality that child classes will extend or utilize, subclassing helps maintain the DRY principle. Beyond this threshold, the consequences warrant careful consideration.

In this tutorial, I’ll demonstrate a method for quantifying inheritance-induced complexity and its impact on change propagation. This approach enables data-driven design decisions and extends to broader software architecture concerns.

This technique leverages graph theory to calculate distances between objects via edge relationships.

Okay, let’s write some code. Inheritance of classes in Swift is denoted by classTemplate:

class A {

}

class B:A {

}

class C:B {

}

class D:C {

}

A -> B -> C -> D

We should envision this scenario as a sequence of interconnected nodes forming a directed graph.

If you don’t know what that is, here’s an article: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Graph_theory

Here we can describe the distance from A using the edges. The distance from D to A is 3 The distance from C to A is 2 The distance from B to A is 1

Furthermore, numerous permutations emerge when examined from different object perspectives, though we’ll focus primarily on A.

Having explored the depth distance from A to D, let’s examine the breadth dimension. Or how about we just subclass from A?

class A {

}

class B:A {

}

class C:A {

}

class D:A {

}

//A -> [C,B,D]

Here the distance between A and CBD is 1, but the width or breadth of A is 3. Does that have an impact on change? If so, whose perspective? Now let’s cut into this a bit deeper. (Exercise left to the reader after completing the article)

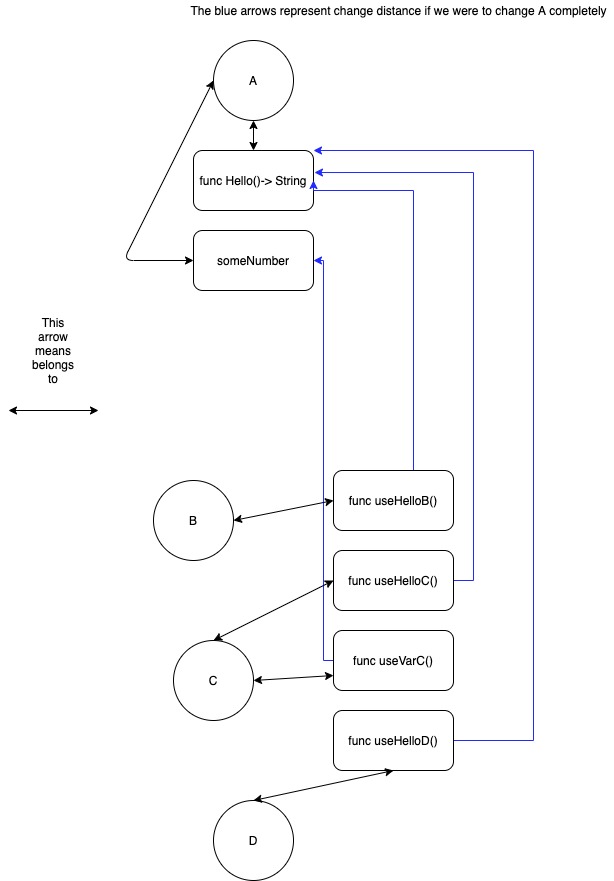

By overlaying this graphical abstraction onto OOP code, we establish a framework for measuring change propagation when modifying functions or variables in A’s design.

How about functions and variables now?

class A {

public var someNumber:Int = 0

public func hello() -> String {

return ""

}

}

class B:A {

}

class C:B {

}

class D:C {

}

Let’s go back to the first example and add a variable to class A and a function func Hello() -> String that returns a string.

By introducing the public variable someNumber to A, we’ve effectively disseminated variables and functions throughout A’s entire inheritance hierarchy.

What does that mean from a graphical perspective?

class A {

public var someNumber:Int = 0

public func hello() -> String {

return ""

}

}

class B:A {

public func useHelloB() {

hello()

}

}

class C:B {

public func useHelloC() {

hello()

}

}

class D:C {

public func useHelloD() {

hello()

}

func useVarC() {

print(someNumber)

}

}

Examining the graph reveals that modifications would cascade through 4 functions and 1 variable while preserving their original behavior.

Should we attempt to eliminate A entirely, the change distance in this contrived design becomes substantial. This stems from the intricate web of dependencies inheritance creates.

When architecting with inheritance, these implications demand careful deliberation.

Design must account for the temporal dimension: how future developers will interface with and extend your architectural choices.

Consequently, as others build upon your foundation, modifying base implementations becomes increasingly arduous without substantial refactoring efforts.

Typically, we would navigate this transition through systematic deprecation.

To minimize complexity, we must shorten the dependency chains between variables while strengthening cohesion—co-locating related functionality to ensure that closely interdependent elements reside together. This reduces the traversal distance between dependent components and minimizes the ripple effects of change across the inheritance hierarchy.

Consider the principle of locality: when methods frequently access the same variables, they should exist at the same inheritance level. This proximity reduces cognitive load—developers don’t need to trace through multiple parent classes to understand interactions. Moreover, it enables easier refactoring since related changes remain localized within a single class boundary.

The inverse relationship between inheritance depth and maintainability becomes clear through this lens. Each additional layer of inheritance increases the conceptual distance between cause and effect, making the codebase progressively more brittle. By flattening hierarchies and favoring composition over inheritance, we create systems where change propagation follows predictable, localized patterns rather than cascading through an elaborate ancestry.

Note: I’ve omitted the nuanced implications of public variable exposure and its compounding effect on complexity.

Note On Example: Additionally, while removing A and modifying Hello() might seem trivial in our examples (given their minimal functionality in child classes), the critical insight remains: these changes must still be propagated throughout the codebase.